Decision service business rules in JBoss Rules

This article describes the kinds of business rules that you might implement in a decision service, with a simple example; this is essentially a functional design.

This article is part 2 of a series:

-

Decision service architecture with JBoss Rules - what a decision service is and gave a high-level technical overview how you can use the JBoss Rules Execution Server to build one

-

Decision service business rules in JBoss Rules - this article

-

How to build a decision service using JBoss Rules Execution Server - how to get this working, with example rules - a RESTful decision service with no Java code required.

Functional requirements

For this example we are going to write business rules for desktop PC configuration, to determine which components can be selected when building a custom PC. The decision service will implement the following business rules:

-

The user must select a motherboard type, a processor type.

-

The user must select memory modules with specific sizes.

-

An empty selection will result in an error message.

-

The selected motherboard type and processor type must be present in a pre-defined list.

-

The selected memory module size must be present in a pre-defined list.

-

The selected processor’s socket type must match the motherboard’s processor socket type.

-

The selected number of memory modules must not exceed the motherboard’s number of memory sockets.

-

Memory modules must be selected in pairs of matching sizes.

-

If the selection violates one of these rules, a message must be generated.

-

The decision service will provide lists of available components: motherboards, processors and memory modules.

-

The lists of available components will only include components that are compatible with any existing selections.

Decision service functionality

The requirements above mean that the decision service will need to provide the following functionality.

-

Define lists of available components.

-

Generate lists of the remaining available components.

-

Generate result messages.

-

Validate that each selection is not empty.

-

Validate that each selection is in the list of available components.

-

Filter available components based on previous selections.

-

Perform additional ad-hoc validations.

Data model

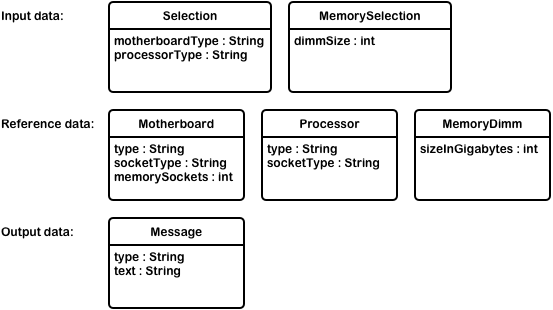

For this example, we shall use the following data model. This includes the input data for the user selections, the reference data for the items in the lists of available components, and additional output data.

Selection has properties for the selected motherboard type and

processor type. In addition, there is a separate MemorySelection for

each memory module selected.

The reference data types Motherboard, Processor and MemoryDimm

each represent a different version of each component, with properties

for their different characteristics. The Motherboard and Processor

type properties are the identifiers specified in the Selection, while

each type of MemoryDimm is identified by size, matching the size in

the MemorySelection.

The output data consists of text messages. The reference data will also be included in the output data, to represent the lists of available components.

Business rules in the Drools Rule Language

Lists of available components

Now it is time to look at the rules code, starting with the lists of available components.

First, I am going to assume that the reference data objects have already been inserted into the rules session’s working memory, to provide the facts that the rules will use to reason about the user’s selection. In this example, we can use additional rules to insert the facts from within the rules session:

rule "Insert motherboards"

when

not Message(text == "Motherboards inserted")

then

Motherboard integrated = new Motherboard();

integrated.setType("integrated");

integrated.setSocketType("none");

integrated.setMemorySockets(0);

insert(integrated);

Motherboard standard = new Motherboard();

standard.setType("standard");

standard.setSocketType("pga");

standard.setMemorySockets(2);

insert(standard);

insertLogMessage(drools, "Motherboards inserted");

endIn practice, however, you would be more likely to do this using the rule session’s Java API:

final List<Command> commands = new ArrayList<Command>();

final List<Motherboard> motherboards = getMotherboards();

commands.add(CommandFactory.newInsertElements(motherboards);

final StatelessKnowledgeSession session = knowledgeBase.newStatelessKnowledgeSession();

session.execute(CommandFactory.newBatchExecution(commands));This means that the following rule would be activated - for example, there are motherboards facts:

rule "Motherboard reference data loaded"

when

$motherboard : Motherboard()

then

System.out.println("Found motherboard: " + $motherboard);

endTo make the lists of these components available as output data, we define queries:

query "motherboards"

value : Motherboard()

endResult messages

Another piece of functionality we need is to generate result messages. For this, we define a new JavaBean type inline in the rules file that has properties for the message text, and a message type that we can use to identify which kinds of messages to include in the output:

declare Message

type : String

text : String

endWe can now use this new type in rules. For example, the following rule

inserts a new message "Found first motherboard" when there is a

Motherboard fact in working memory. This only happens once, because

the left-hand side also checks that the message itself is not yet in

working memory.

rule "First motherboard reference data loaded"

when

Motherboard()

not Message(text == "Found first motherboard")

then

Message message = new Message();

message.setType("DEBUG");

message.setText("Found first motherboard");

insert(message);

endSince the Message type only has a default constructor, it is somewhat

verbose to insert the message; it is more convenient to define a

function in the rules file:

import org.drools.spi.KnowledgeHelper

function void insertDebugMessage(KnowledgeHelper drools, String text) {

Message message = new Message();

message.setType("DEBUG");

message.setText(text);

drools.insert(message);

}To make a certain type of messages available in the output, we just define another query:

query "messages"

value : Message(type == "RESULT")

endValidating user selections

The user selections are String properties in the Selection type. The

first validation is simply to check that the selection is not empty:

rule "No motherboard selected"

when

Selection(motherboardType == null)

then

insertMessage(drools, "No motherboard selected");

endIn general, a good way to name a rule is to summarise the condition that

its left-hand side represents - the same kind of self-documentation as

good method names in Java. However, in the previous validation rule this

means that the message duplicates the rule name, which is bad. We can

easily avoid the duplication by adding another utility function that

gets the rule name from the drools helper object:

function void insertRuleNameMessage(KnowledgeHelper drools) {

insertMessage(drools, drools.getRule().getName());

}Next, using the new insertRuleNameMessage function, the selection’s

motherboardType should match the type property value of an available

motherboard:

rule "Selected motherboard type does not exist"

when

Selection($type : motherboardType != null)

not Motherboard(type == $type)

then

insertRuleNameMessage(drools);

endFiltering available components

So far the validation rules have not been very interesting, in the sense that they would be just as easy to implement in Java. However, things get more interesting if we start changing which facts are in working memory.

In PC configuration, selecting one component may affect what you may choose for another component. In our example, selecting a particular processor rules out motherboards with an incompatible processor socket.

rule "Filter motherboards for selected processor socket type"

when

Selection($processor : processorType != null)

Processor(type == $processor, $socket : socketType)

$motherboard : Motherboard(socketType != $socket)

then

retract($motherboard);

endThis rule has three left-hand side conditions. First, the selection must

specify a processor type, which is bound to the $processor variable.

Second, there must be an available processor that has the selected

processor type; its socket type is also bound to a variable. Finally,

there is a motherboard that has a different socket type, which is also

bound to a variable. This rule matches against each such motherboard,

and the right-hand side removes the matched motherboard from working

memory, filtering the list of available motherboards.

The interesting thing about this rule is that as well as filtering the

list of motherboards that are returned by the motherboards query

defined above, this affects which motherboards are available for the

Selected motherboard type does not exist rule. The selected

motherboard type might initially have been in the list of available

motherboards before being filtered out, resulting in the message

"Selected motherboard type does not exist".

A crucially important thing to consider when implementing these kinds of

rules is that you do not have to care about what order these things

happen in - you do not have to think about making sure the filtering

happens first. This is because when the filtering rule modifies working

memory by retracting the motherboard, the rules engine automatically

re-evaluates the validation rule’s not Motherboard(type == $type)

condition, which may now be true.

In a more realistic example, there would be many more complex dependencies between components, such as powerful graphics cards requiring a second or larger power supply, which in turn means needing a larger physical case.

Ad-hoc validations

Beyond the kinds of basic validations described above, which apply to all kinds of selections, a real-world problem will always have additional validations that do not fit into any kind of pattern. This is where you get the most benefit from using a rules engine, because each special case can just be an additional rule that uses the same working memory data as other rules.

For example, a special rule for memory modules is that they must be

selected in matched pairs of the same capacity. In other words, there

must be an even number of each size selected. In our model, each

individual memory module is a separate MemorySelection fact, so we

count them using the built-in collect function:

import java.util.ArrayList

rule "Memory must be selected in matching pairs"

when

MemorySelection($selectedDimmSize : dimmSize)

ArrayList($quantitySelected : size) from collect( MemorySelection(dimmSize == $selectedDimmSize) )

eval($quantitySelected % 2 != 0)

then

insertRuleNameMessage(drools);

insertMessage(drools, $quantitySelected + " x " + $selectedDimmSize + "GB DIMMs selected");

endAgain, there are three left-hand side conditions. The first condition

matches against a selected memory module, and binds its size to a

variable. The second condition uses the collect function to collect

all MemorySelection facts that have that size into a

java.util.ArrayList, and binds the number of facts in the list (the

quantity of selected memory modules) to a variable. The third condition

then evaluates a Java expression that is true when the quantity is an

odd humber.

The rule inserts the rule name as a validation message, as usual, as well as an additional message that indicates which size was not selected in matched pairs.

One problem with this version of this rule is that it generates

duplicate messages. Suppose that the selection includes three

MemorySelection facts with size 8GB. The rule’s second condition will

get the value 3 and the third condition will be true because three is

odd. However, the first condition will cause the rule to be activated

three times, once for each of the three MemorySelection facts, which

means that the right-hand side will execute three times. One way to

solve this would be to add a condition that the message "3 x 8GB DIMMs

selected" is not in working memory. Alternatively, in practice, the

MemorySelection facts might be ordered in some way so that you can add

a condition that only matches on the 'first' one.

Next steps

Once you have written some business rules for your decision service, the next step is obviously to run them and test them. The simplest way to do this is to configure the JBoss Rules Execution Server to load the rules file, so that you can execute the rules using its web services interface.