Own goals - Scala vs Ceylon vs Kotlin

For various reasons, there is a lot of discussion going on about new programming languages that run on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Some of the discussion about Scala, Ceylon and Kotlin includes the idea that we do not need all three. After all, if you want to use a better language than Java, one will do, right?

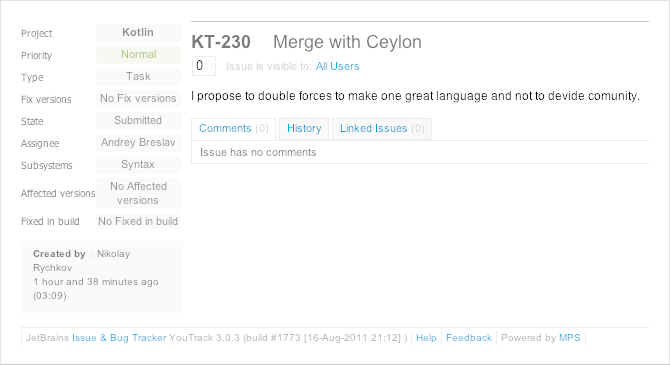

For example, the following joke task (now pulled) on the Kotlin project’s issue tracker suggests merging with Ceylon.

As far as I can tell, the many discussions comparing the languages aren’t really going anywhere because language design is about tradeoffs. These discussions also miss the point: it is more interesting to ask what the projects’ goals are.

Scala goals

You might think that the Scala language is designed to get the largest number of PhD students involved in the project. A more reliable source is the interview with Martin Odersky, inventor of Scala, in which he says:

The first thing we cared about was to have as clean an integration of functional and object-oriented programming as possible.

The first chapter of the book Programming in Scala explains this in more detail, starting with the name:

The name Scala stands for “scalable language.” The language is so named because it was designed to grow with the demands of its users. You can apply Scala to a wide range of programming tasks, from writing small scripts to building large systems.

This desire for scalability is what leads to mixing object-oriented and functional programming:

Technically, Scala is a blend of object-oriented and functional programming concepts in a statically typed language. The fusion of object-oriented and functional programming shows up in many different aspects of Scala; it is probably more pervasive than in any other widely used language. The two programming styles have complementary strengths when it comes to scalability. Scala’s functional programming constructs make it easy to build interesting things quickly from simple parts. Its object-oriented constructs make it easy to structure larger systems and to adapt them to new demands. The combination of both styles in Scala makes it possible to express new kinds of programming patterns and component abstractions. It also leads to a legible and concise programming style.

The notion of concise code is the first thing that the Scala web site mentions:

Scala is a general purpose programming language designed to express common programming patterns in a concise, elegant, and type-safe way.

To summarise: Scala’s goal is to let you write a certain kind of code.

Ceylon goals

Compared to the Scala goals above, the goals listed in the Introduction to Ceylon are broader:

to be easy to learn and understand for Java and C# developers,

to eliminate some of Java’s verbosity, while retaining its readability,

to improve upon Java’s typesafety,

to provide a declarative syntax for expressing hierarchical information like user interface definition, externalized data, and system configuration, thereby eliminating Java’s dependence upon XML,

to support and encourage a more “functional” style of programming with immutable objects and higher-order functions,

to provide great support for meta-programming, thus making it easier to write frameworks, and

to provide built-in modularity.

You might think that this is a bit like saying that the goal of Ceylon is to make it easier to write Hibernate. The grain of truth in this is that Ceylon goals are clearly a result of experience with how Java has been used over the last ten years, which differs greatly from its original design.

Summary: Ceylon’s goal is to design the language that Java would have been if its designers had been able to predict the future.

Kotlin goals

The Kotlin documentation page also includes a list of design goals:

to create a Java-compatible language,

that compiles at least as fast as Java,

make it safer than Java, i.e. statically check for common pitfalls such as null pointer dereference,

make it more concise than Java by supporting variable type inference, higher-order functions (closures), extension functions, mixins and first-class delegation, etc;

and, keeping the useful level of expressiveness (see above), make it way simpler than the most mature competitor – Scala.

Since Kotlin comes from JetBrains, you might think that this all has something to do with IntelliJ IDEA, their IDE. According to their own explanation of Why JetBrains needs Kotlin, you’re not wrong:

Although we’ve developed support for several JVM-targeted programming languages, we are still writing all of our IntelliJ-based IDEs almost entirely in Java. We want to become more productive by switching to a more expressive language.

In other words, the goal of Kotlin is to make it easier to write IntelliJ IDEA. Of course, while you’re at it, it’s worth trying to get the rest of the world to use the language so they also buy JetBrains’ tools. In other words:

The next thing is also fairly straightforward: we expect Kotlin to drive the sales of IntelliJ IDEA.

Summary: the goal of Kotlin is to let us all carry on doing what we were already doing, but with more productivity and better tools.

Conclusion

Despite obvious differences, all three projects seem to agree on several things; code should:

-

run on the JVM

-

be type safe

-

be more concise than Java.

The first difference is that only Scala and Ceylon list introducing functional programming as a project goal. At least, that is the impression you get from a first glance at the goals lists. However, this is merely a difference in emphasis, instead of an actual difference in what we can expect from the languages. Dmitry Jemerov from the Kotlin team wrote in to say that functional programming (FP) is 'more of a "duh" than an explicit goal - so obvious for us that FP support is needed’. This is somewhat unexpected: we seem to have progressed from a period in which it went without saying that new languages be object-oriented to a time when it is ‘obvious’ that new languages integrated object-oriented and functional programming styles.

The second difference is that only Ceylon and Kotlin want to be simpler and easier to learn than Scala. Despite the fact that Scala seems to be an easy target for being ‘too hard’, this is actually a rather subtle point. Scala’s designers sincerely believe that Scala is as simple and easy to learn as it is possible for it to be, and are committed to keeping the language as simple as possible. The crucial point is that Scala subscribes both to the notions ‘as simple as possible’ and ‘no simpler than that’.

In the eyes of its designers, Scala cannot be any simpler than it already is, and it is this that the Ceylon and Kotlin projects seem to disagree with. In other words, all three projects seem to agree that a language should be as simple as possible, but both the Ceylon and Kotlin projects believe that it is possible to be more simple than the Scala project does.

Only time will tell whether Ceylon and Kotlin actually manage to be simpler or easier to learn than Scala when they are ‘finished’, and whether they will have become less useful than Scala in the process.