GPU Programming For The Brave

Introduction

GPUs, some might call them graphic cards, have never been a stranger for video gamers. The evolution of GPUs significantly changed not just the video game industry, but also the field of parallel programming.

I was lucky enough to participate some courses that briefly introduced GPU programming during my master study. As my first humble attempt, I hereby write down my knowledge and understanding about GPU programming in this blog post. Hopefully, after reading this write-up, you can have a basic idea about: how GPUs work, how to do some simple GPU programming and why it is so important to the field of AI.

What is GPU

GPU is the abbreviation of "graphics processing unit". It is a specialized electronic circuit designed for digital image processing and to accelerate computer graphics, being present either as a discrete video card or embedded on motherboards, mobile phones, personal computers, workstations, and game consoles.

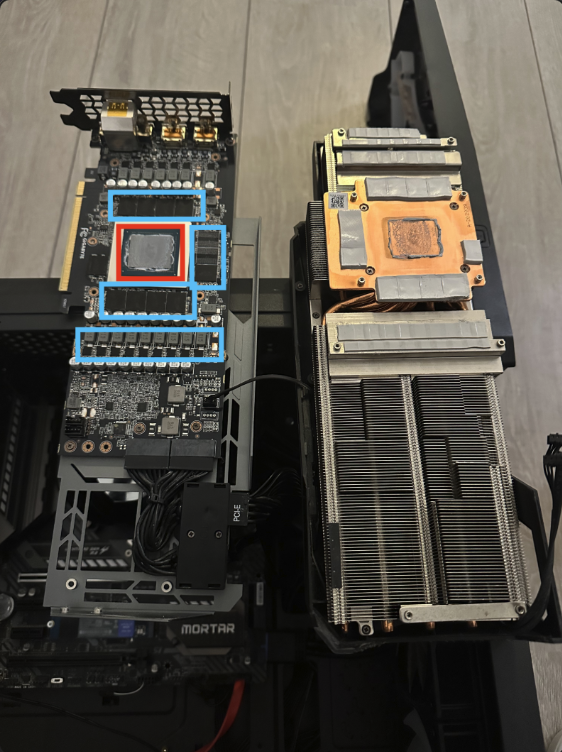

If you have tried to build your own PC, you will probably call the big gas-stove-look-a-like thing in Figure 1 a GPU. However, this is not entirely correct. Graphics card is a more suitable name for it. And if you have ever had a chance to disassemble a graphics card like me, then I am sure you will notice there are much more than just a GPU on a graphics card. The GPU itself is only a small part on it and there’s memory, power supply and cooling unit. The composition resembles any normal PC you can see. Figure 2 is taken when I had an GPU memory overheating issue. As you can see in the picture, the GPU is surrounded by the red box and blue boxes for the GPU memory. The part on the right is the cooling unit.

The small exercise

There is no way we can actually know how to do GPU programming by just looking at the composition picture. To help with the understanding, let’s consider a small code exercise where you have to implement a simple fill_matrix function in C to fill a rectangle shape within a two-dimensional matrix with some certain value:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void fill_matrix(int **s, int x_len, int y_len, int draw_start, int draw_end, int value_to_fill) {

// IMPLEMENT ME

}

void print_matrix(int **s, int x_len, int y_len) {

// doesn't matter...

}

int64_t initialize_matrix(int rows, int cols) {

// doesn't matter...

}

int main() {

int **s = (int **)initialize_matrix(10, 10);

printf("before: \n");

print_matrix(s, 10, 10);

fill_matrix(s, 10, 10, 2, 8 9);

printf("after: \n");

print_matrix(s, 10, 10);

return 0;

}C version

Easy, isn’t it? All we need to do is to use two nested for-loops to fill the value when the loop arrives the expected range:

void fill_matrix(int **s, int x_len, int y_len, int draw_start, int draw_end, int value_to_fill) {

for (int i = 0; i < y_len; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < x_len; j++) {

if (i > draw_start && i < draw_end && j > draw_start && j < draw_end) {

s[i][j] = value_to_fill;

}

}

}

}If you would like to speed up your implementation, you can even use OpenMp to turn your it into a multi-threaded implementation by simply adding #pragma omp parallel for collapse(2) on top of the outer for-loop. After re-compiling and running export OMP_NUM_THREADS=4, your program should automatically delegate the execution of the for-loop to at most 4 threads.

Now it seems like we really pushed to the boundary, and couldn’t get any more speedup unless increasing the number of threads. However, what we have seen so far is still in the realm of CPU programming, where your code gets executed by the CPU. Besides that, the time complexity of the implementation is O(n*m), which is not a very pleasant number. So let’s try to make use of the power of GPUs, with which we could achieve O(1) complexity.

CUDA version

|

Tip

|

You might find it helpful to temporarily forget what you have learnt about |

__global__ void fill_matrix_kernel(int* matrix, int rows, int cols, int draw_start, int draw_end, int value) {

int row = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int col = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (row > draw_start && row < draw_end && col < draw_end && col > draw_start) {

int idx = row * cols + col;

matrix[idx] = value;

}

}

int main() {

const int rows = 10;

const int cols = 10;

const size_t size = rows * cols * sizeof(int);

// Host memory

int* h_matrix = (int *)malloc(size);

// Device memory

int* d_matrix;

cudaMalloc((void **)&d_matrix, size);

// Define grid and block dimensions

dim3 block(32, 32); // 256 threads per block

dim3 grid(

(cols + block.x - 1) / block.x, // ceil(cols/block.x)

(rows + block.y - 1) / block.y // ceil(rows/block.y)

);

// Launch kernel

fill_matrix_kernel<<<grid, block>>>(d_matrix, rows, cols, 2, 8 9);

// Copy result back to host

cudaMemcpy(h_matrix, d_matrix, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

// Verify values

print_matrix(h_matrix, rows, cols);

// Cleanup

free(h_matrix);

cudaFree(d_matrix);

return 0;

}Above is the CUDA implementation. CUDA is a C-like programming language provided by Nvidia. Naturally, it only runs on Nvidia cards. To compile the code above, we can simply run nvcc -o code_example code_example.cu just like when compiling C code using gcc. Then, the code_example it produces also isn’t any different from other native executable, which could be run by the command ./code_example.

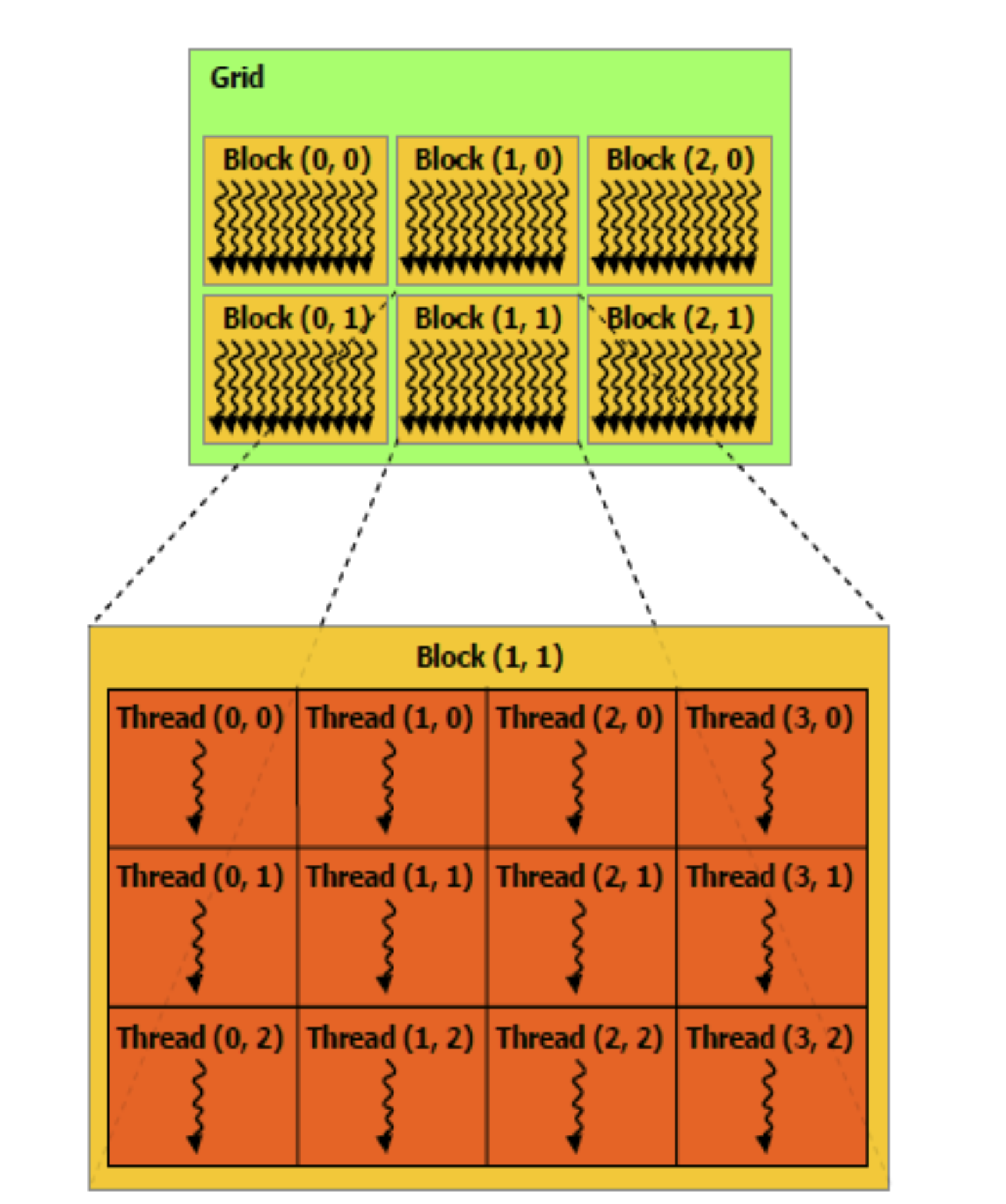

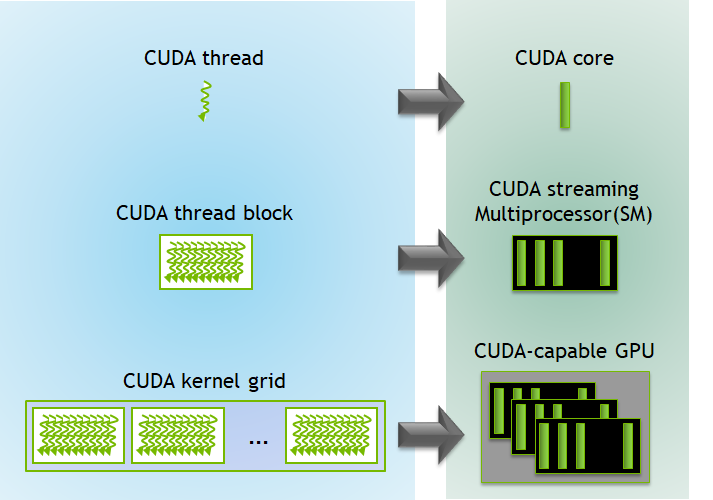

So what happens when we run it? Besides allocating memory on the device, which is our graphics card, the computation kernel (the fill_matrix_kernel function) is executed by all the GPU threads that we requested simultaneously. In the example, we define a grid of one block ((10 + 32 - 1) / 32 = 1) with 256 threads on it. GPU threads are fundamentally different from the CPU threads we know. By design, the number of GPU threads on a GPU is much larger than the number of CPU threads on a CPU. On top of that, what is executed by CPU threads is completely dependent on how you program it. On contrast, GPU threads provides high-throughput due to the nature of simultaneous execution for a kernel. Therefore, we need a way to control the behavior of each GPU thread. Luckily, an unique threadId is assigned to each GPU thread within the same block and each block has a unique blockId. What we can do is to see if the the current thread is within the drawing range and fill the value accordingly based on the location of the thread (blockId * number of blocks + threadId) , which is exactly what the if clause is doing.

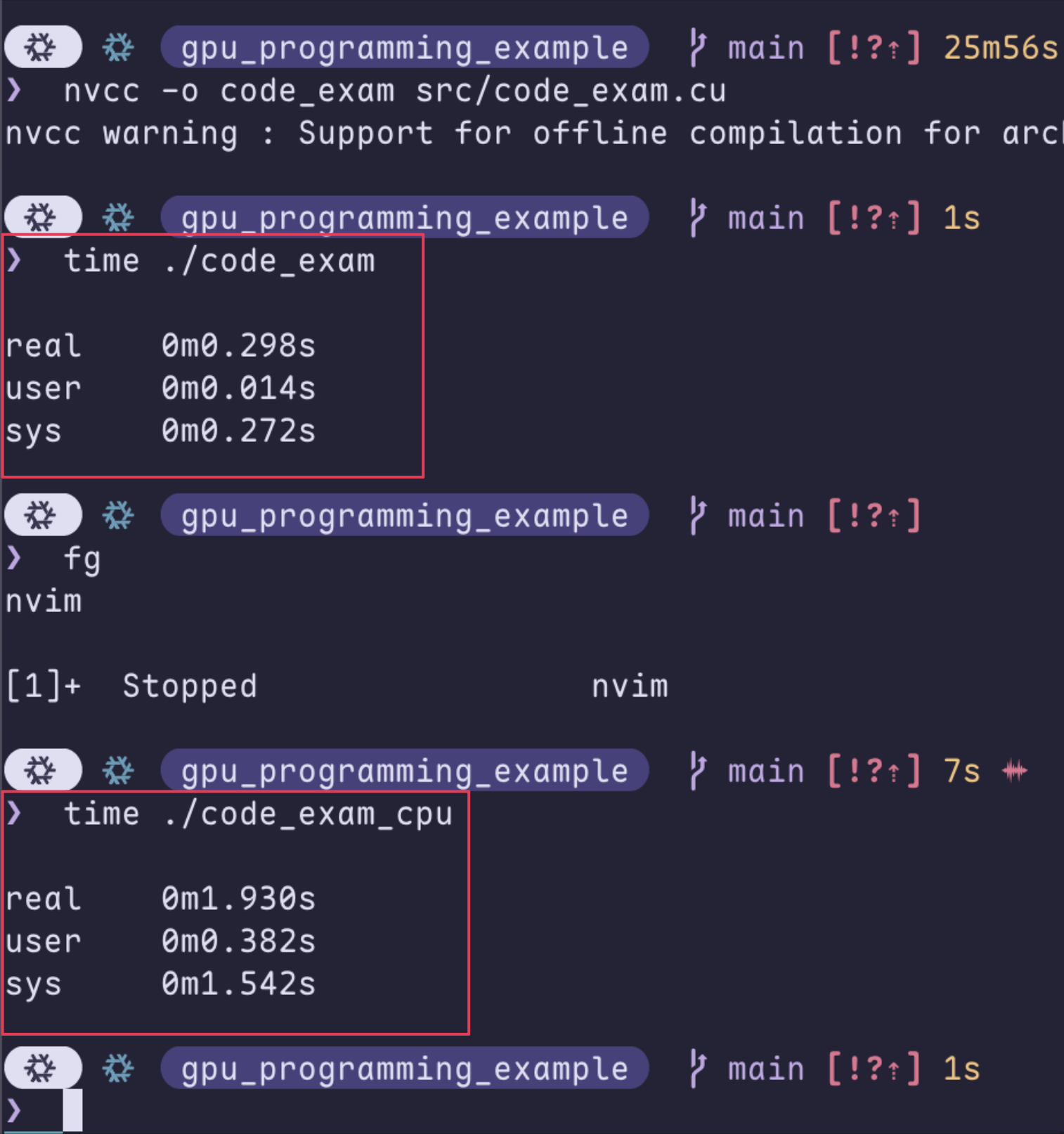

If we leave out the main() function, the actual implementation is only 6 lines and there is no loop being used at all. But how much faster it really is? When running with the matrix shape of 32768 * 32768, our CUDA implementation can finish it within 0.3 seconds while the C implementation needs 1.9 seconds.

Impressive, isn’t it? But trust me, everything seems reasonable when you actually see the difference of thread numbers:

| Intel® Xeon® 6966P-C Processor | AMD Ryzen Threadripper PRO 9995WX | Nvidia RTX 5090 |

|---|---|---|

192 threads in total |

192 threads in total |

21760 CUDA threads |

|

Tip

|

This code example might be too simple and too boring for you. But if you think of the matrix that we are filling as a screen, and the value as RGB value — We are actually rendering a screen! |

Okay, but why AI?

As you might have heard, GPUs are widely used in the field of AI. Given the high-throughput trait of GPU, the process of AI model training can be significantly facilitated. But why is that?

Look into the AI

Thankfully, Wikipedia made it a lot easier for me to explain AI:

"The largest and most capable LLMs are generative pretrained transformers (GPTs), which are largely used in generative chatbots such as ChatGPT or Gemini."

"A GPT is a type of LLM and a prominent framework for generative artificial intelligence. It is an artificial neural network that is used in natural language processing by machines.".

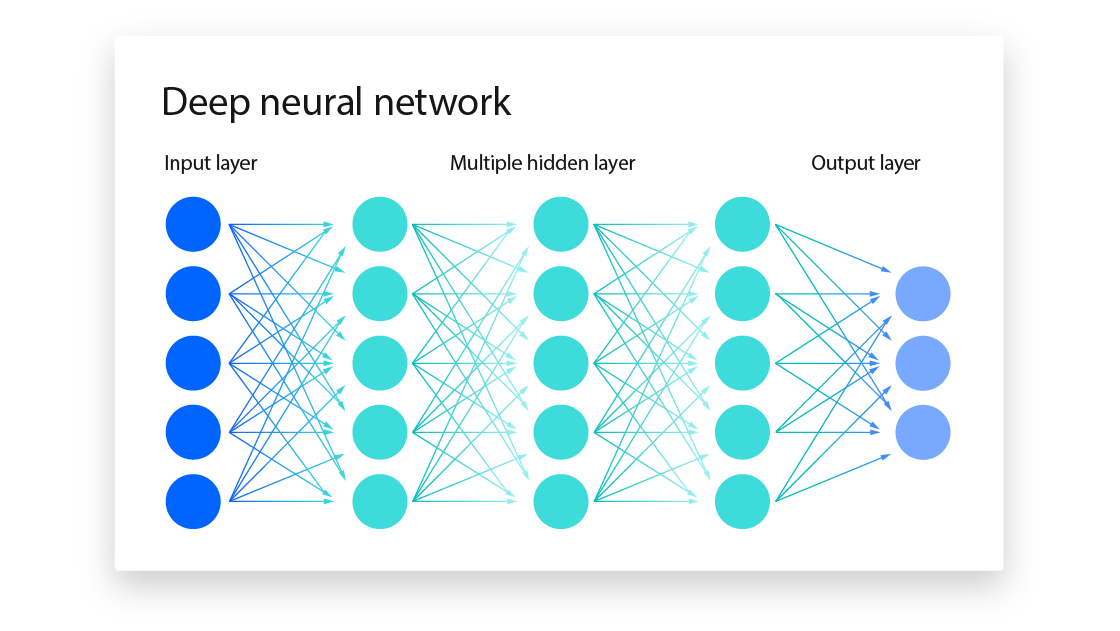

To put it simply: most of the popular AIs are made of neural networks. A neural network is composite of multiple layers of nodes. The first layer takes input from the outside world, normally as the format of a vector of numbers. The output of a layer consists of the output number from each node, which is calculated by summing the input times the weight of the node (sum(input * weight)). And all the subsequent layers take input from the previous one. The process of training the neural network aims to find the weights for each nodes so that the output is most acceptable. And it requires to feed the input → calculate the output → compare with the expected output → adjust the weights repetitively.

We can let GPU run this

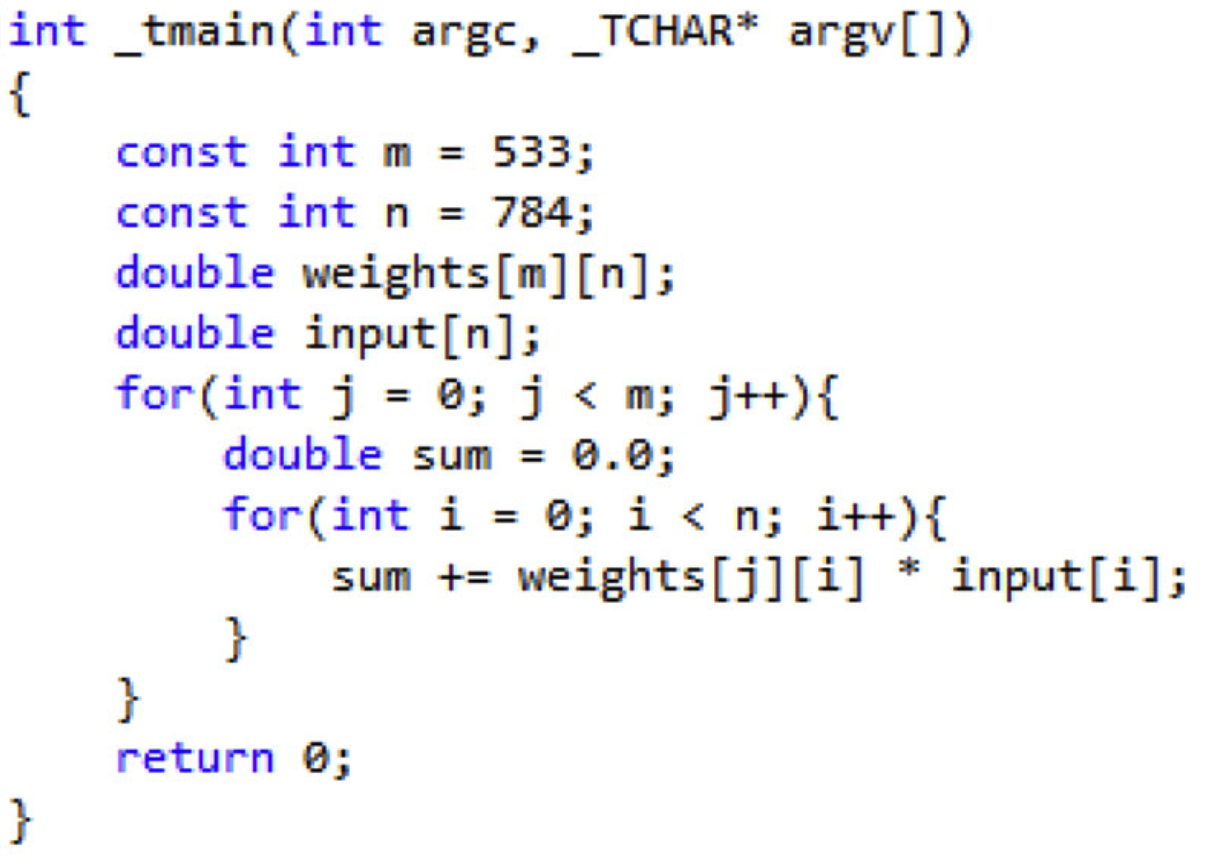

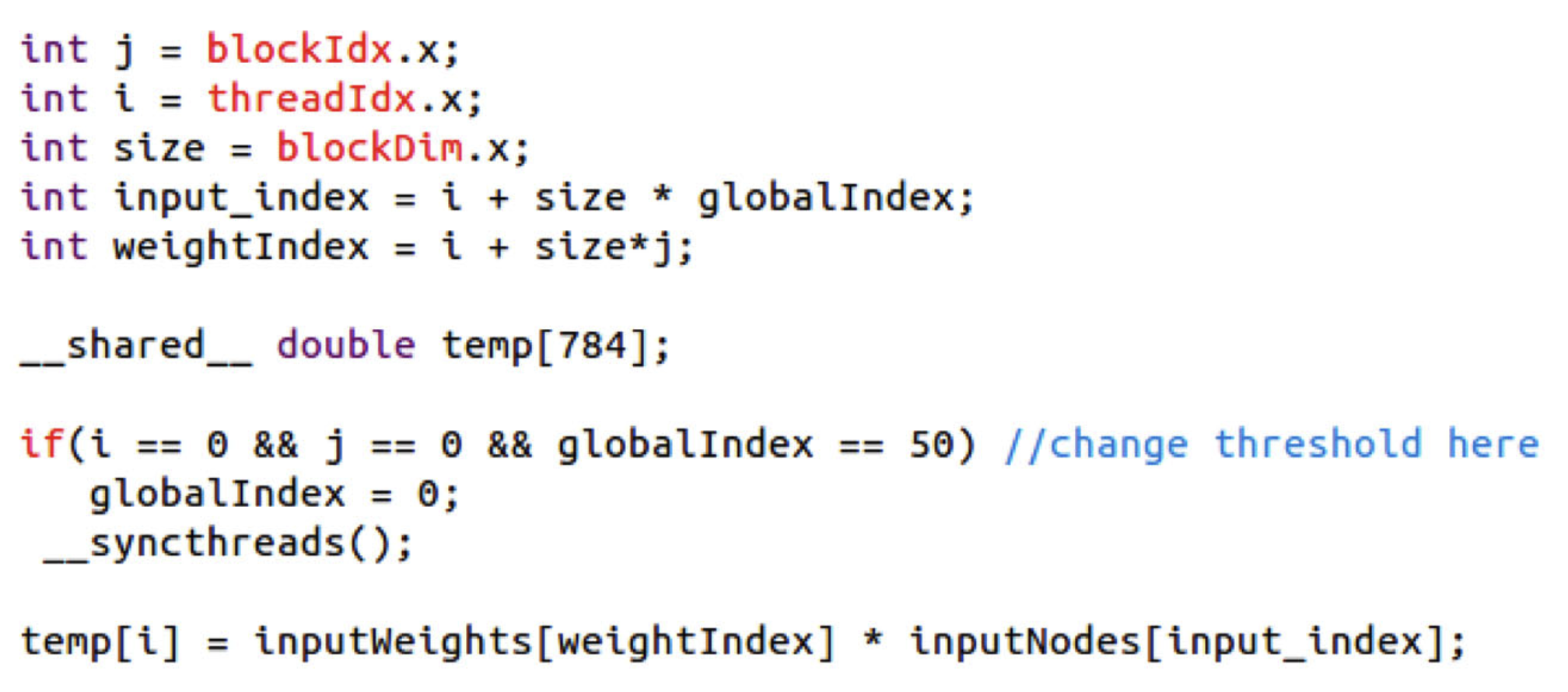

If we try to write a simple implementation, or even pseudo code, of how things are done in each layer of a neural network, we could arrive at what is shown in Figure 7. Once again we see a pattern we have seen just before: a linear algebra calculation wrapped by two for-loops. Therefore, we can easily rewrite to a CUDA implementation shown in Figure 8.

Both Figure 7 and Figure 8 are taken from a research article by Ricardo Brito et al[[1]]. The authors managed to utilize the high-throughput of GPU to accelerate the training process of a neural network in the year of 2016. Except for the countless open-source repositories that implement CUDA-based neural networks, Nvidia offers cuDNN as a GPU-accelerated library of primitives for deep neural networks. Popular neural network frameworks like PyTorch and TenhsorFlow can operate on GPU devices without any extra effort.

To sum up

GPUs, which are originally made for graphics processing, has shown a huge potential in the field of parallel programming and AI training due to their high-throughput nature. This is achieved by piling significant amount of GPU threads and impose simultaneous execution of the compute kernel. Even though it’s not quite possible to assign GPU threads for different execution routine like CPU threads, we can still do minimum control-flow manipulation based on their threadId. Several examples of CUDA, which is a C-like GPU programming language offered by Nvidia, are also shown to demonstrate its syntax.

Finally, you can checkout the code examples I used in this GitHub repo.

References

-

[[[1]]] Brito R., Fong S., Cho K., Song W., Wong R., Mohammed S., Fiaidhi J. "GPU-enabled back-propagation artificial neural network for digit recognition in parallel". The Journal of Supercomputing. 72, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-016-1633-y